"Entre Av' e Eva gran departiment' á":

Cada moneda tiene dos caras . . .

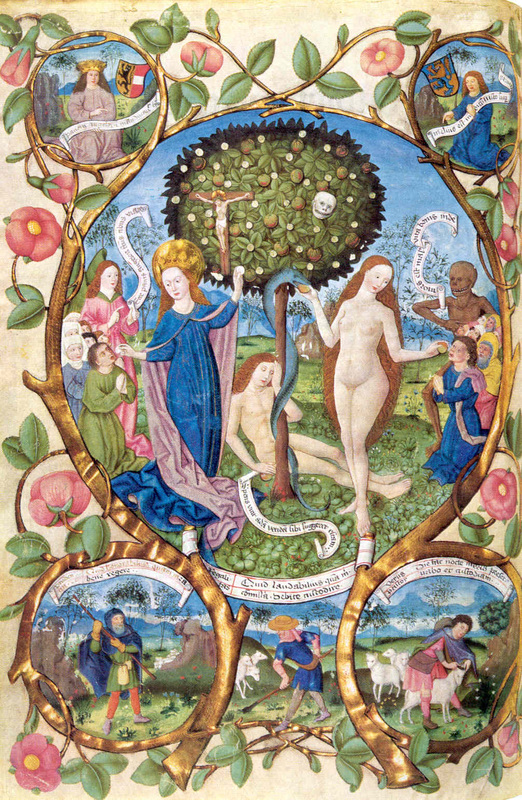

Desde el siglo II, los pensadores de la Iglesia han escrito sobre el paralelismo que existe entre Eva, la madre de los vivientes, y María, la madre de Dios (Gambero). Sin embargo, a principios de la Edad Media, este paralelismo se convirtió en una dicotomía tajante y florecía una nueva onda del culto mariano. Según José María Izquierdo, en ese momento había “una crisis de los sistemas normativos feudales en toda la Europa occidental” frente a la cual la Iglesia Católica reaccionaba con un deseo ardiente de proteger el estatus sagrada del sacramento de matrimonio y de la familia, la base de una sociedad sana (59). Incluido en esta ambición era una preocupación con la sexualidad de la mujer como crucial en mantener la naturaleza sacrosanta del núcleo familiar. Escribe Izquierdo que, “[se hizo] necesaria una reformulación de la visión que de la mujer se tenía tradicionalmente como fomentadora del caos en el mundo desde el relato mítico del libro del Genesis. A partir de ahí y siguiendo el modelo exegético de la Iglesia el caos del pecado introducido en el mundo por una mujer deberá ser neutralizado por otra mujer que introduzca el orden, la redención, en el mismo” (59). Entonces, lo que se sugería es que había dos modelos principales que la mujer medieval podía seguir: el modelo positivo de María, o el modelo negativo de Eva. Otro bono de confiar en la Virgen María es que ella incluso puede redimir a la mujer que previamente ha descendido al nivel de Eva.

Como resultado de esta nueva obsesión con el marianismo, “se creó en las incipientes literaturas de las lenguas románicas el tema de la oposición Ave/Eva o lo que es lo mismo entre María, la Nueva Ave dadora de vida, y Eva, madre de la estirpe humana introductora de la muerte tanto física como espiritual en forma de pecado” (Izquierdo 60). Una de las maneras en que esta oposición se manifestaba en la literatura medieval era a través de la paranomasia anagramática de los nombres Ave y Eva (Izquierdo 60).

Como resultado de esta nueva obsesión con el marianismo, “se creó en las incipientes literaturas de las lenguas románicas el tema de la oposición Ave/Eva o lo que es lo mismo entre María, la Nueva Ave dadora de vida, y Eva, madre de la estirpe humana introductora de la muerte tanto física como espiritual en forma de pecado” (Izquierdo 60). Una de las maneras en que esta oposición se manifestaba en la literatura medieval era a través de la paranomasia anagramática de los nombres Ave y Eva (Izquierdo 60).

paronomasia (paranomasia).

(Del lat. paronomasĭa, y este del gr. παρονομασία).

4. f. Ret. Figura consistente en colocar próximos en la frase dos vocablos semejantes en el sonido pero diferentes en el significado, como puerta y puerto; secreto de dos y secreto de Dios.

- Real Academia Española

anagrama.

(Del lat. anagramma, y este del gr. ἀνάγραμμα).

1. m. Transposición de las letras de una palabra o sentencia, de la que resulta otra palabra o sentencia distinta.

2. m. Palabra o sentencia que resulta de esta transposición de letras; p. ej., de amor, Roma, o viceversa.

- Real Academia Española

(Del lat. paronomasĭa, y este del gr. παρονομασία).

4. f. Ret. Figura consistente en colocar próximos en la frase dos vocablos semejantes en el sonido pero diferentes en el significado, como puerta y puerto; secreto de dos y secreto de Dios.

- Real Academia Española

anagrama.

(Del lat. anagramma, y este del gr. ἀνάγραμμα).

1. m. Transposición de las letras de una palabra o sentencia, de la que resulta otra palabra o sentencia distinta.

2. m. Palabra o sentencia que resulta de esta transposición de letras; p. ej., de amor, Roma, o viceversa.

- Real Academia Española

Izquierdo define la paranomasia anagramática como una fusión de estos dos elementos, la paranomasia y el anagrama (60). Se usa los anagramas ‘Ave’ y ‘Eva’ dentro de una técnica retorica que es una variación de la paranomasia: los anagramas se colocan muy cerca el uno al otro, no dentro de la misma frase necesariamente (aunque a veces esto también ocurre) sino dentro de la misma historia o unidad narrativa. Dice Izquierdo que, “La paranomasia anagramática Ave/Eva es el resultado de la visión teológica del mundo, del poder de la palabra en las sociedades fundamentadas en las religiones del libro y de la preminencia de la imagen sonora y plástica en una sociedad de iletrados analfabetos como era la medieval” (60). La idea es que con la profunda semejanza visual y auditiva entre ‘Ave’ y ‘Eva’, le mención de una de las dos necesariamente convoca la imagen de la otra y todos los aspectos que la define, como ocurre en el caso del Prólogo de Los Milagros de Nuestra Señora de Berceo.

El “poder de la palabra” y “la preminencia de la imagen sonora y plástica” sigue siendo prevalente en literatura y arte contemporánea, igual como el paralelismo/dicotomía entre Eva y María. Sin embargo, la manera en que éste se manifiesta y se interpreta no es siempre la misma, y tampoco es uniforme:

El “poder de la palabra” y “la preminencia de la imagen sonora y plástica” sigue siendo prevalente en literatura y arte contemporánea, igual como el paralelismo/dicotomía entre Eva y María. Sin embargo, la manera en que éste se manifiesta y se interpreta no es siempre la misma, y tampoco es uniforme:

|

A Dream of Comparison (Stevie Smith - siglo XX)

After reading Book Ten of 'Paradise Lost' Two ladies walked on the soft green grass On the bank of a river by the sea And one was Mary and the other Eve And they talked philosophically. 'Oh to be Nothing,' said Eve, 'oh for a Cessation of consciousness With no more impressions beating in Of various experiences.' 'How can Something envisage Nothing,?' said Mary, 'Where's your philosophy gone?' 'Storm back through the gates of Birth,' cried Eve, 'Where were you before you were born?' Mary laughed: 'I love Life, I would fight to the death for it, That's a feeling, you say? I will find A reason for it.' They walked by the estuary, Eve and the Virgin Mary, And they talked until nightfall, But the difference between them was radical, |

Cantiga 60 "Entre Av' e Eva" (Alfonso X - siglo XIII) Entre Ave y Eva hay una gran diferencia. Pues si Eva nos arrebató el Paraíso y a Dios, con el Ave (María) nos lo dio; por lo tanto, amigos míos: Eva nos echó en la prisión del demonio, y el Ave nos sacó de ella; y por este motivo: Eva nos hizo perder el amor y la gracia de Dios, y el Ave nos lo hizo recobrar; y por eso: Eva nos cerró los cielos sin llave, y María abrió las puertas por el Ave. |

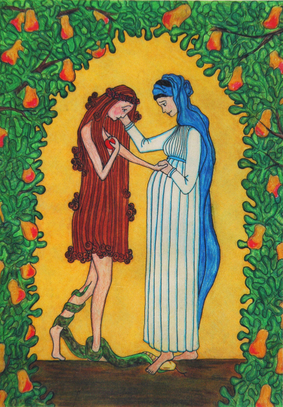

La Cantiga de Alfonso X se enfoca en la Ave como redentora benevolente. Contrapone a las dos mujeres y comunica muy claramente que María está en una posición superior de gracia y pureza, y que tiene que encontrar una manera de negar o redimir las acciones desafortunadas de Eva. El poema de Stevie Smith no niega las diferencias ideológicas entre las dos mujeres. Sin embargo, en contraste la Cantiga, no sugiere que la diferencia fundamental entre las dos mujeres es necesariamente negativa. No obstante la imposibilidad de llegar a un acuerdo mutua en cuanto a sus filosofías personales, las dos mujeres siguen caminando juntas al lado del río y hablan hasta el atardecer. El dibujo de Smith es interesante, porque, aunque el poema trata un descuerdo ideológico, el dibujo muestra a las dos mujeres con las manos entrelazadas, casi en la postura de un abrazo. Esto parece indicar que no obstante sus diferencias, puede existir una suerte de amistad o coexistencia entre las dos madres de la humanidad, y que, más que valorar una sobre la otra, sería posible apreciar las influencias que transmiten las dos, entrar en un dialogo entre opiniones, y apreciar lo que cada una aporta a la vida humana.

Perspectivas históricas del paralelo Ave-Eva

|

San Justino (Justino el mártir), en el siglo II, era muy probablemente el primero en escribir sobre el paralelismo entre la primera mujer y la madre de Dios (Gambero 46).

San Justino escribió:

|

|

Ireneo de Lyon, también en el siglo II, escribió:

|

|

Efrén de Siria, en el siglo IV, escribió:

|

|

|

Epifanio de Salamis, en el siglo IV, escribió:

|